Arnheim expounds on light in Art and Visual Perception upon gestalt grounds: brightness is a relative affair. Reflectances of surfaces are not sufficient to see them accurately, and perceived brightness can be manipulated through relative contrast and spatial arrangement. Space structures light, as when we take illumination into account and recognize the constant lightness of a surface across the shadows projected upon it. In an opposite way, shape can be induced from light, as in Mach's card shown above.

Although Arnheim notes the salience of shadows for structuring light, he also notes their rarity in world art as naturalistic devices. Indeed, many traditions do without naturalistic light, as the medieval west with its otherworldly golds. Arnheim only briefly talks about the ability of an artist like Rembrandt to suggest illumination - glowing - in his paintings and it is this kind of perceptual phenomenology of the "filmy," the non-objectual, that has been of more interest recently. We have already touched upon the Ganzfeld as the limiting condition of perception where, significantly, the absence of figural objects gives rise to an experience of a foggy ground-like quality.

[Olafur Eliasson, The Weather Project, 2003, Monofrequency lights, projection foil, haze machines, mirror foil,

aluminium, and scaffolding, 26.7 m x 22.3 m x 155.4 m]

In searching for the liminal experience of light, artists have been interested in the nature of light and its paradoxical effects. Perhaps the most emblematic case of searching after a kind of meta-light is Olafur Eliasson's creation of a surrogate sun in his Weather Project at Tate Modern. By creating an artificial environment in which visitors can recreate the experience of sunlight, he poignantly provides also a commentary on the surrogate experiences of nature found in postmodernity and hints at dystopian ideas of a sun extinguished, which must be recreated by humanity.

[Donald Judd, 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986; https://www.chinati.org/collection/donaldjudd]

It is easy, however, to overemphasize the point of a meta-reality and suggest that artists are only concerned with ideas of nature, or portraying them in an ironic way. One could say such things of Donald Judd, whose one hundred machined steel boxes in Marfa, Texas, stand aloof like simple industrial objects. Yet as Adrian Kohn has pointed out, such polished surfaces produce a riot of perceptual effects over the course of a day, as the illumination changes and the colors of the ambient light play on the slick surfaces [1].

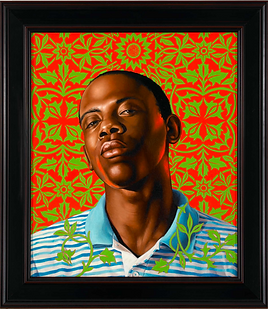

[Kehinde Wiley, James Quin, Actor, 2008, Oil on canvas, 26" X 22"]

The formal concerns over induced glowing and luster in painting can be connected to larger issues of identity. Krista Thompson has discussed the way in which a "shine" aesthetic can be observed in African diasporic communities, emphasizing the shiny as a mode of insertion into the public sphere [2]. Shine mimics the pricey surfaces of new automobiles and the flash of photography of the paparazzi. Kehinde Wiley's portraits of young men reflect the aggrandizing practices of classic western art but also utilize the bright, tapestry-like backgrounds and slick oil surfaces of past art to frame his subjects in a glow that signals their overdue arrival into the canon of art history.

[1] Adrian Kohn, "Judd on Phenomena," Rutgers Art Review 23 (2007): 79–99.

[2] Krista Thompson, Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice (Duke University Press, 2015).